PATERNAL MEMOIRS

|

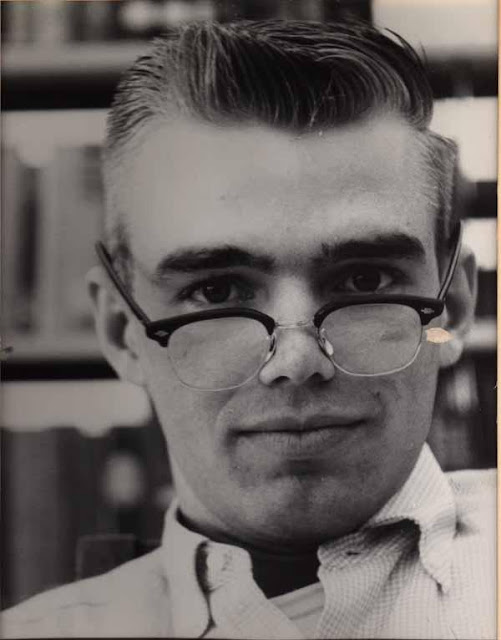

| Kenneth Casstevens, circa 1960. Photo by Ann Casstevens |

My father was Dr. Kenneth Rodgers Casstevens at the University of Texas at Tyler. He was a college professor, complete with the sweater and the tie that match the stereotype. His students called him “Mister Rogers” because he did rather resemble Fred Rogers in that ensemble.

When he wasn’t dressed for work, Dad was in his jeans, work boots, and a straw cowboy hat, working in the yard or the house. Or welding on something he needed for whatever it was he was doing.

My first visit to the Alamo was with my father. He had been a Texas history teacher in the beginning of his educational career. On day trips to Austin, we would stop on the way at the Stagecoach Inn in Salado to eat, and he would tell me about how people traveled around Texas in the early days of the Republic, and how people stopped in Salado and had for nearly 200 years.

“Texas was a country first. Then it was a part of the United States,” he said. "We are not like other Americans." Like my fellow Texans, I have not forgotten that.

When I came home from school angry at the rudeness of a boy in my class, my father was the one who said, “He was brought up in New York. They aren’t known for having manners. But then again, it could just be that he doesn’t know any better. I teach with his father. The apple seldom falls far from the tree. I think that is how they must speak to one another up there. I’ve never met one that wasn’t like that. But I will say this: you always know where you stand with them. They might be rude, but they do tend to be honest. I appreciate that part.”

My classmate’s father was the man who, in faculty meetings at the university, opened every comment with, “Your problem is that the way you do things in Texas is wrong. In New York…”

Fed up with the man’s rudeness, my father quietly said, “Well, you know, you could go home to New York. We’d all pitch in and help you pack. I’ll buy the pizza for the lunch break. I think we can get you ready to go in a day.” He was gone within six months, home to New York.

I have since had the pleasure of meeting some very gracious, charming New Yorkers.

They have made Texas their permanent home. Seldom do stereotypes apply consistently, I am happy to report.

My father was brutally honest. If he thought I was slipping in some way with regard to upright moral behavior, he’d point it out and would not waste time with tact. It bordered on the cruel at times, but he felt he had a reason to do it. I was in the fourth grade when I lied about my homework and I forged my mother’s signature on a teacher’s note that I knew would get me in trouble if she read it. Honesty came at a price at my house. But dishonesty came at a higher one. And teachers talk to parents.

I got in the car when he picked me up from school and his first words to me were, “How do you sleep at night?” I will spare you the rest of what he said. It was as ugly as it gets and I expected to get thrashed pretty hard when I got home. But this time, he handed me the Tyler phone book and told me to count the number of people listed with the names of Smith (1,427) and Jones (1,608). Then he had me count the number of people with the name Casstevens. There was only one listed, and that was us.

“Remember that, because people remember your name. You have to remember who you are and who you come from. People will remember if you are untrustworthy. And right now, you very much are.”

My father valued integrity above all else. He was very slow to trust others. Displays of affection or emotion made him uncomfortable. He was not one for deep, personal conversations about feelings. But he would go on at length about the virtue of being someone others could look to for strength and courage.

Dad had a dry, clever sense of humor. He loved practical jokes. April Fool’s Day was his favorite holiday. His secretary, Carolyn, was a saint. Every year for 18 years, she endured his planting rubber snakes or plastic cockroaches all over her office for her to “discover.” He’d hide them and wait for her to scream, which I am sure she did. They were buddies (as much as you could be with my father if he allowed you) for all those years they worked together and into his retirement.

Dogs were the only “people” who had my father’s deep trust. He liked them better than people. They are, after all, faultlessly loyal, completely honest, and they don’t talk trash about you behind your back. Of course, he could be himself with them.

He loved “westerns.” Movies, books, or televisions shows, my father watched them all. As a boy, he’d follow the serials in the movie theaters, starring Hoot Gibson, Roy Rogers, and Gene Autry. He memorized Gene Autry’s “Ten Commandments of the Cowboy” which are:

1. The Cowboy must never shoot first, hit a smaller man, or take unfair advantage.

2. He must never go back on his word, or a trust confided in him.

3. He must always tell the truth.

4. He must be gentle with children, the elderly, and animals.

5. He must not advocate or possess racially or religiously intolerant ideas.

6. He must help people in distress.

7. He must be a good worker.

8. He must keep himself clean in thought, speech, action, and personal habits.

9. He must respect women, parents, and his nation's laws.

10. The Cowboy is a patriot.

He adored science fiction with the same passion. I think part of his love affair with computers sprung from that. He believed that computers would change the way we communicate. So in 1980, he requested to purchase computers for the media center at the University of Texas at Tyler. The request was denied, so he resubmitted the request listing the computers instead as “media hardware.” The request was granted, and UT Tyler got their first computers.

“It is after all ‘hardware,’” Dad said.

I came to believe that being a Texan was synonymous with who my father was as a man.

My father often quietly stood up for what was right even when it was unpopular to do so. He backed his instructors in his department at the university when they were right and the administration was wrong. He refused to compromise his values. He never saw the need to put on any other image than his own genuine one.

My father and I were never close. He only ever once told me he loved me that I recall, in an email. I wish I had kept it, but at the time, we were at odds with one another, and I trashed it.

He would die a year later from cancer after writing it. His last words to me the last time we saw each other were, “I hope you know how much your mother loves you.”

I was not with him when he died. The regret runs deep. But even had he lived, we would not be any closer. It was not possible to get close to him. He was who he was: intense, private, potently angry when provoked, honorable, stoic, and the eternal cowboy, though he was a white collar professional all of his adult life.

The best way to describe my father is that he was much like Mark Harmon’s character Jethro Gibbs of the television show, NCIS. I cannot watch the show without seeing my father in every mannerism, style of speech, and facial expression. Had he been buried rather than cremated, I would have asked that his only epitaph be: “This was the last honest man the world will ever know.”

A friend of my father’s from their college days wrote my mother, upon learning of my father’s death, this:

“Since receiving your message on the passing, I have spent some time reflecting on my memory of him. Believing that Ken built on the personal values he demonstrated in the '60s, he left a legacy that is certainly to be admired. Ken's life was , anchored in integrity...no room for compromise... honesty...gentle...the ultimate professional...trustworthy... holding values that made up the America we like to remember. In the words of J. Frank Dobie, ‘He would do to ride the river with.’ He was a faithful dependable friend.”

Comments

Post a Comment